The burial for our pre-born son, Doloran Simeon Suberlak, came and went in a blaze of beauty. Krzys had contacted a Polish priest from a local parish and he was happy to come to the cemetery and say the prayers. The Polish priest was warm, and so were the prayers of the Church. They were in Polish, but Krzys whispered the translation to me as we stood close together over the burial plot. I really needed to hear the words of the Church speaking to me through a priest. He said, roughly speaking: “We bury this child in the hope of the Resurrection.”

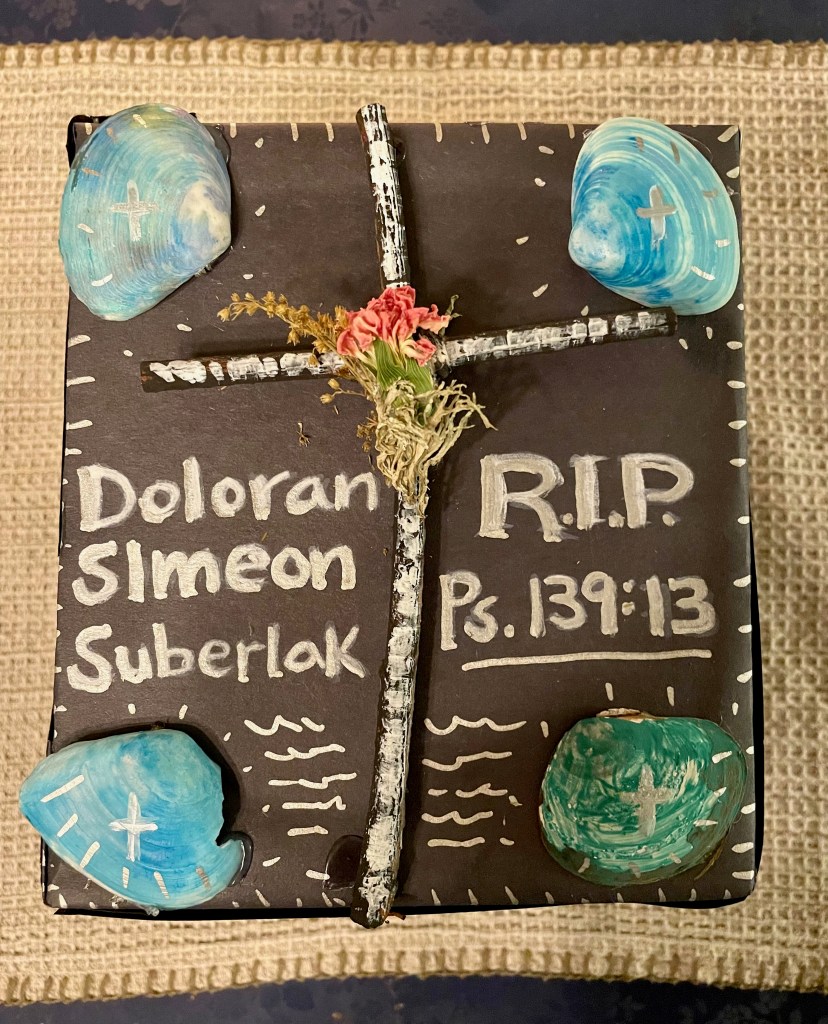

I did kneel down and place the box myself, which I had decorated last night with shells and a wooden cross, and scriptures and words of hope. Though I started this little project with some diffidence, the very act of daubing paint on a “sarcophagus” that contained my own child, immediately brought forth tears. I must admit there has never been a more primal experience of art-making.

I cried and blessed the box with my tears after the Father blessed it with holy water. I felt the tears were a special kind of holy water from a mother. And so I said these words, as loud as a could, so my tears wouldn’t drown out the words:

“Dear Doloran, my tiny son.

Your time with us in this world was so short. Yet God willed you to exist, he created you within our family and we love you. We ask you to pray for us and for the siblings that preceded you in death within my womb: Noah Jonah and Andrew Noel.

God gave us a great gift in that I was able to birth your tiny body with the pains that come as a mother’s privileged cross, and we were able to see you, hold you and kiss your tiny form.

We greatly desire your baptism, and have done our best to provide for your salvation. We pray for this and will always do so while we live.

Now we have the honor of laying your mortal remains to rest in hollowed ground, and we pray that whatever graces may flow from this will be applied to your siblings who were not able to be buried in this way.

We ask all this in Jesus’ name and by the special intercession of your patroness, Mary, Our Lady of Sorrows.

Psalm 139: 13-16

For you created my inmost being;

you knit me together in my mother’s womb

I praise you because I am fearfully and wonderfully made;

your works are wonderful,

I know that full well.

rame was not hidden from you

when I was made in the secret place,

when I was woven together in the depths of the earth.

Your eyes saw my unformed body;

all the days ordained for me were written in your book

before one of them came to be.”

Then I threw the first clod of dirt on the box and led us in singing the “Stabat Mater” while they covered it with dirt. Then me and the girls knelt down and decorated the spot with shells from the beach they had collected and little dandelions and different things they found.

I know we can’t put anything permanent without paying thousands of dollars for a headstone, and they warned us that they will throw everything away after we leave. But shells from the beach and leaves and wildflowers are free. I made a cross from the purple shells and I plan to keep adding crushed shells in the form of the cross. I know even a mower won’t pick that up! And if they manage to get it out of the grass I’ll just keep putting it back. There is no shortage of shells from the beach.

I may be poor but I’m determined. Krzys laughed that morning as I was crushing purple shells to take to the cemetery: “Oh yeah tell an ARTIST she can’t leave anything permanent. That’s just a challenge!”

Doing this brought a lot of consolation. Just seeing the priest standing there as we approached the site, and the sexton (not sure if this is the right word, but it feels better to say than “grave-digger”), and someone from the cemetery organization, all of whom had it all set up for us to do everything in the proper way—and all for free by the way—I felt incredibly loved. And I was able to accomplish the public part of grieving for this child.

This is a rare gift in cases when children die in utero. With this kind of death, the isolation is the hardest part. How do you talk about losing a child you never quite had? So doing this was a very special medicine indeed, and I might not have done it, had I not been encouraged by other Catholics to try. It was important, too, to include intentions for the other two babies, who didn’t get a burial. And to be able to do the artistic things myself.

Burying the dead is a real work of grace—even with a little death like this one. A little person, a little birth, a little death, a little burial, a little grieving. That’s what this is like for me. To be honest, it doesn’t feel like I lost a child I knew, rather, it feels like I lost the chance to know a child I would have fiercely loved. A child I do love in a primordial, speechless way.

The bond with one’s own pre-born baby is a bond more basic than fondness. It sits deeper than personality. It is a bond made irrevocably but not yet fully realized. The satisfaction of loving is in knowing the other, but I can’t really know Doloran as I know my living children. And that is perhaps the real source of the pain.

Yet, he was a part of me, and part of him will always remain in me. This is physically true as well as it is spiritually true. His cells will literally remain in me for the rest of my life. This grief is different than if he were already born, but it is very much a child-loss. It’s a hidden kind of loss. Hidden even from my own conscious mind much of the time. But making it less hidden, as we have deliberately done here, makes it feel less like shame, and more like nature—and nature is good.

God is good, his creation is orderly, and we can rejoice in it. Doing these things for Doloran and for the other babies is the only way I can love them. It’s like my midwife said when I was going through the contractions with this miscarriage: “embrace it—this is your moment with this little guy.” That’s why I’m grateful even for the pain, because it means I do love this baby. This is my way of loving him.

Leave a comment